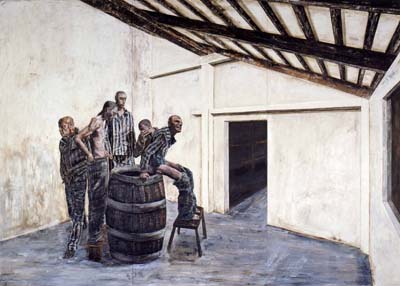

Latrine, Poland 1944, 2002 oil on canvas , 350 x 480 cm Ronald Ophuis The Kiss of War Recent Paintings For the question "Can you show everything?" Ronald Ophuis (1968) substitutes another one, "Can you put everything in pictures?" AEROPLASTICS contemporary art gallery is presenting this young Dutch artist's recent oil paintings, uncompromising visions of humankind divided into victims on the one hand and tormentors on the other. Two men in combat uniforms are playing with a ball in a filthy toilet, disregarding the man crouching on the ground at their feet and bathed in a pool of blood. In a cloakroom, three teenagers hold a fourth one down on the ground and sodomise him with a (large) Coca-Cola bottle. Note that all of them are wearing the same football team uniform. These works by Ronald Ophuis are part of a series of paintings done between 1995 and 1997 and exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam in 1999 under the title "Five paintings about violence". They won the artist rapid fame in the country of Vermeer, especially when he went to court to oppose the state's demand that a child abuse scene ("Sweet violence") be withdrawn from a public exhibition - and won his case! The court thus did not go along with the opinion of the visitors who had equated this atrocious picture with child pornography, but it is not certain that such a ruling would have been handed down everywhere. Wasn't Sally Mann, in those distant times, accused of paedophilia for her photographs of her naked daughters and son? In Ophuis' work, choosing children reflects the will to express violence using an uncompromising vocabulary that leaves no doubt as to his intentions. For the message can prove more ambiguous, as in the scene of a young girl in her bathing suit who is lying at the water's edge and masturbating a naked boy in a gesture that we suspect - without being certain - is forced upon her. Or then again the collective shower, with three men who are coating their penises with liquid soap, most likely not just to wash, but nothing tells us if everyone has agreed to take part in what will follow. These few works enable us to pin down Ronald Ophuis' very characteristic style. His aggressive staging and rooting of several of his themes in contemporary history (World War II, Rwanda, Chechnya, etc.) recall Marcus Lüpertz, Jörg Immendorf and Anselm Kiefer. The very large canvases show life-sized figures, even if in the child rape scene the little girl's abnormally small size underscores her total lack of defence against her assailant. And it is indeed a staging, in the strict sense of the word, that we have before us, for the artist had actors mime for him the situations that he was going to paint. Moreover, these documents are exhibited at Aeroplastics in an amazing confrontation between the photographs and their re-presentations. The approach recalls that of Rodin, who was accused of having moulded his "Saint-John the Baptist" on a live body and who proved, studio photos in hand, that he worked from a model. While Rodin's detractors got satisfaction, the viewer standing in front of Ronald Ophuis' paintings will doubtless appreciate that they were not painted from photographs of actual events. But to what extent are the scenes that they portray actually imaginary? It would be mistaken to compare them to the images of daily violence that a certain branch of the press delights in disseminating. Such pictures, when they exist, luckily if we dare say so are more likely to find themselves in the category of exhibits for the prosecution. Just think of the pictures that the juries and audiences of trials such as the trials of the perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide were subjected to. There are, however, some sadly famous exceptions that allow the public to be confronted with images of the type that Ronald Ophuis merely invents, such as those taken of the "Rape of Nanking", when the Japanese massacred thousands of Chinese civilians upon taking the city in 1937. With just a few exceptions (a film shot by a witness at the risk of losing his own life), the soldiers themselves took the photographs as souvenirs of the nameless savagery that they unleashed on the population of women, children, and old people. It is significant to note that the painter prefers to create his own idea of violence from scratch. A more recent series concerning the Nazi concentration camps poses the question of staged pictures more keenly. For while, following the example of the Nanking pictures, we are aware of the countless pictures taken by the tormentors at Auschwitz and Birkenau, none of them show what Ophuis chose to depict, namely, prisoners in the grip of dysentery or prisoners committing a rape on a barrack's floor in Birkenau, as if trying to surpass their jailers. In contrast, the suicide of Mala Zimetbaum, who is shown lying down against an immaculate backdrop, her gaze turned heavenwards, takes on the trappings of redemption. The paintings of Vann Nath, one of the few survivors of the Khmer Rouge prison of Tuol Sleng, are striking because of the contrast between their quasi-naïve style and the intolerable violence to which they attest. But that is just it. The painter is a witness - a position that Ophuis, in his quest for more dizzying heights of horror, rejects. (Pierre-Yves Desaive, Brussels, March 2003) Catalogue available: Ronald OPHUIS "One to One". With gracious thanks to The MONDRIAN FOUNDATION for their support. 22 March - 24 May 2003 Hours: Wed-Sat 2 - 7 pm aeroplastics contemporary Rue Blanche 32 / Blanchestraat B-1060 Brüssel Telefon +32 2 537 22 02 Fax +32 2 537 15 49 E-Mail aeroplastics@brutele.be www.aeroplastics.net |