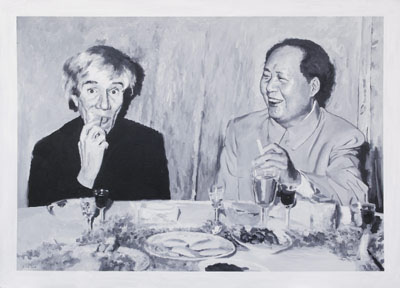

Untitled (Warhol), 2006 Öl auf Leinwand, 185 x 133 cm / 72.83 x 52.36 inch Shi Xinning Polyphony Click for English text Die Galerie Arndt & Partner freut sich, die erste Einzelausstellung des chinesischen Künstlers Shi Xinning in Europa zu präsentieren. Wenn es ein Genre der chinesischen Gegenwartskunst leichterdings ins Bildgedächtnis des Westens geschafft hat, dann ist es der Mao-Pop. Andy Warhol und Gerhard Richter haben diesbezüglich mit ihren Adaptionen von Mao-Porträts gute Vorarbeit geleistet. Bereits auf der legendären, ersten offiziell genehmigten Ausstellung aktueller chinesischer Kunst in Pekings Nationalgalerie (China/Avant-Garde, Februar 1989) sorgte Wang Guangyi mit einem Porträt Mao Zedongs, über das er ein rotes Gittermuster malte, für Aufregung. Es folgten Künstler wie Xue Song, bei dem lediglich die markante Kontur Maos bestehen bleibt, oder Yu Youhan, der Propagandabilder entpolitisiert, indem er sie mit folkloristischem Blumendekor überzieht. Der in Peking lebende Maler Shi Xinning, geboren 1969 als Sohn eines Offiziers der Volksbefreiungsarmee in der nordöstlichen Provinz Liaoning, distanziert sich ausdrücklich von dieser Kunstströmung. Seine im Jahr 2000 begonnene Serie von in Öl auf Leinwand oder Acrolein gemalten Bildern, in denen ein idealtypisch energischer Mao in Gesellschaft von Hollywood-Stars, Künstlern oder Persönlichkeiten der Politik anzutreffen ist, argumentieren nicht rückwärtsgewandt, sondern erzählen fiktive oder, wie er es nennt, "utopische" Geschichten. Shi Xinning vergleicht seine künstlerische Arbeit mit der eines Regisseurs. Oftmals fungieren Zeitungsabbildungen als Grundlage für seine Settings. Sich der Bildsprache der Pressefotos annähernd, bemüht er sich um einen nahezu unsichtbaren Pinselduktus und eine abgeschwächte Farbigkeit. In einem nächsten Schritt entwickelt Shi Xinning die narrative Handlung, tauscht Gegenstände oder Personen der Vorlage gegen andere aus, fügt Neues hinzu und definiert die Lichtregie. "Ich arbeite fast immer mit der Zusammenschau völlig unvereinbarer Versatzstücke. So lasse ich beispielsweise Mao eine Duchamp-Ausstellung besuchen - die es in China nie gab -, platziere einen Stahlschwung von Richard Serra auf dem Platz des Himmlischen Friedens und zwar mit Blickrichtung auf Maos berühmtes Porträt am Eingang zur Verbotenen Stadt oder arrangiere das Treffen einer Mao-Statue mit der New Yorker Freiheitsstatue. […] Es geht mir nicht um Mao Zedong als reale Person. Mao ist aber auch heute noch eine Ikone in China. Er ist omnipräsent, er hat meine Kindheit geprägt und das Leben meiner Eltern. Ich zeige ihn nie im realen Kontext der 60er und 70er Jahre, ich zeige ihn als visualisierte Erinnerung." Geschichte als Kontinuum von drei bis 5000 Jahren, das für den Einzelnen umstandslos bis heute Anknüpfungspunkte an die eigene Gegenwart bietet und Geschichtsentsorgung, die das Verhältnis zu Mao auf die Formel "70"> seiner Taten waren gut, 30"> schlecht" (Deng Xiaoping) reduziert: beide Haltungen führen in China eine friedliche Koexistenz. Da die nicht-offizielle Geschichtsschreibung eine nur schwache Tradition hat, kommt nicht zuletzt der chinesischen Gegenwartskunst die Vermittlerposition zwischen diesen beiden Extremen zu. Bei allem Leid, das die Kulturrevolution über Chinas Volk gebracht hat, und ungeachtet Maos ausdrücklicher Intellektuellen- und Kunstfeindlichkeit, thematisieren Bilder wie die von Shi Xinning den Stolz, den auch heute noch viele Chinesen für den Grossen Vorsitzenden hegen. Anlass für einen derartigen Heroismus bieten u. a. der Lange Marsch, die Etablierung einer neuen staatlichen Ordnung, die Aufwertung des Bauernstandes und die unermüdliche Forcierung eines chinesischen Kollektivgeistes. Hinter seinen Verdiensten verblassen seine Fehler. Es seien "die Fehler eines grossen proletarischen Führers", so eine ZK-Resolution Über einige Fragen unserer Parteigeschichte aus dem Jahre 1981. Shi Xinnings Mao-Verhältnis ist ambivalent - dessen ist er sich wohl bewusst. In seinen Bildern gestaltet er diese Spannung in Form von Paradoxen: Mao trifft die Beatles, bewundert den von Christo verhüllten Reichstag und - kaum zu steigern - wohnt einer Nackt-Performance zeitgenössischer chinesischer Künstler bei. Utopisch ist Shi Xinnings Kunst nicht im Sinne eines Vorscheins einer erwünschten Versöhnung antagonistischer Wertsphären, sondern als rein ästhetisches Ausagieren kontrafaktischer Geschichtsmomente. Ulrike Münter (Auszug aus dem gleichnamigen Aufsatz in der die Ausstellung bei Arndt & Partner Berlin begleitenden Publikation) Ausstellungsdauer 4.9. - 30.10.2007 Oeffnungszeiten Di-Sa 11 - 18 Uhr Galerie Arndt & Partner Zimmerstrasse 90-91 D-10117 Berlin Telephone +49 (0)30 280 81 23 Fax +49 (0)30 283 37 38 Email berlin@arndt-partner.com www.arndt-partner.com Shi Xinning Polyphony Arndt & Partner is pleased to present the first solo show of the Beijing-based artist Shi Xinning in Europe. Among the genres of contemporary Chinese art, none is more deeply ingrained in the visual memory of the West than that of Mao Pop. The way to this state of affairs was paved by adaptations of Mao portraits by Andy Warhol and Gerhard Richter. As early as the first officially sanctioned exhibition of contemporary Chinese art in China's National Art Gallery in Beijing (China/Avant-Garde, February 1989), Wang Guangyi's portrait of Mao Tse-tung - overlaid with a grid of red paint - proved controversial. Then came artists such as Xue Song, who reduced Mao to a mere contoured outline, and Yu Youhan, who depoliticizes propaganda images by embellishing them with folksy floral motifs. The Beijing-based painter Shi Xinning explicitly distances himself from this tradition. The son of an officer in the People's Liberation Army, he was born in 1969 in the northeastern province of Liaoning. In a series of oil paintings on canvas that he has been working on since 2000, an idealized energetic Mao is seen in the company of Hollywood stars, artists and political figures. But these works do not present retrogressive arguments. Instead they tell fictitious or, as he calls them, utopian stories. Shi Xinning compares his work as an artist with that of a film director. He often uses newspaper images as the basis for his paintings. In keeping with the visual qualities of these media images, he employs barely visible brushwork and a washed out, muted palate. Shi Xinning then develops his narratives, substituting objects or people in the original with his own selections, adding elements that were not there in the original, and adjusts the lighting of the scenes. "I almost always work with a staging of completely incompatible props and scenery. For example, Mao views a Duchamp exhibition in China - something that never took place. Or I place a curved steel sculpture by Richard Serra in Tiananmen Square - facing Mao's famous portrait at the entrance to the Forbidden City. Or I arrange a meeting between a Mao statue and New York's Statue of Liberty. […] I am not interested in Mao Tse-tung as a real person. Today, Mao is still an icon in China. He is omnipresent; he defined my childhood and the lives of my parents. I never show him in the real context of the 60s or 70s. I present him as a visual memory." History is either a three- to five-thousand-year continuum that can enable individuals to define their place in the present, or something that can be willfully revised to produce formulas that summarize the deeds of Mao as: "70"> good, 30"> bad" (Deng Xiaoping). Both positions coexist peacefully in China. As the critical study of history has not really been established there, a further role for contemporary art in China is that of a mediator between these two extremes. Images by artists such as Shi Xinning scrutinize the pride and reverence with which many people in China still regard Chairman Mao today - despite all the misery that the Cultural Revolution brought to the Chinese people, not to mention Mao's hostility towards intellectuals and the arts. Such heroism focuses on the Long March, the establishment of a new national order, the valorization of the rural poor, and the tireless forging of a collective Chinese spirit. Mao's mistakes are eclipsed by his achievements. They are "the errors of a great proletarian leader," according to a 1981 Central Committee resolution "on some questions concerning the history of our party." Shi Xinning's relationship to Mao is ambivalent - a fact he is acutely aware of. His images represent this tension in the form of paradoxes: Mao meets the Beatles, admires Christo's wrapped Reichstag, and - in a gesture that is hard to top - attends a nude performance by contemporary Chinese artists. If Shi Xinning's art is utopian, this is not because it illustrates a desire for the reconciliation of antagonistic value systems. On the contrary, the artist's ideals are acted out on a purely aesthetic level in nonexistent moments of history. Ulrike Münter (excerpt from her essay published in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition) Exhibition 4 September - 30 October 2007 Gallery hours Tues-Sat 11 am - 6 pm |