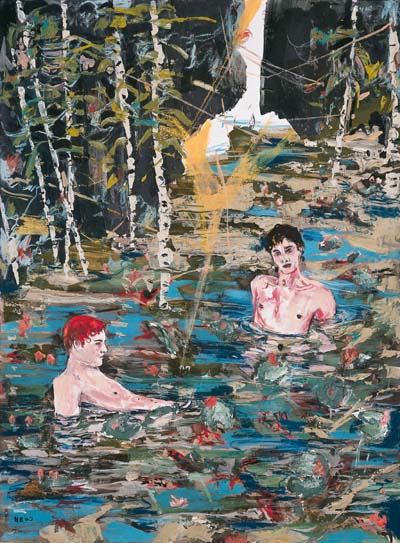

Hernan Bas: Untitled (Koi Pond), 2005 Wunschwelten Neue Romantik in der Kunst der Gegenwart David Altmejd, Hernan Bas, Peter Doig, Kaye Donachie, Uwe Henneken, Karen Kilimnik, Justine Kurland, Catherine Opie, Christopher Orr, Laura Owens, Simon Periton, David Thorpe, Christian Ward Click for English text Intimität und Geborgenheit sind in einer Gesellschaft, die durch wachsende Mobilität und das Schwinden sozialer Bindungen geprägt ist, zu den Inhalten einer neuen Sehnsucht geworden. Darüber hinaus lässt die Übersättigung mit schlechten Nachrichten und Bildern des Terrors das Verlangen nach Orten der Sicherheit und rettenden Perspektiven wachsen. Diese Situation spiegelt sich auch in der aktuellen bildenden Kunst wider. Nach den diskursanalytischen Untersuchungen der 1980er und 1990er Jahre und der Umfunktionierung von Kunst zu sozialer Handlung trifft man überall auf eine Wiederbelebung des traditionellen Werks. Künstler wie Peter Doig, Laura Owens, Uwe Henneken, David Altmejd, Kaye Donachie, Karen Kilimnik, Justine Kurland oder David Thorpe knüpfen entschlossen an einen romantischen Geist an. Hinter der Sehnsucht nach dem Paradiesischen, Schönen und Märchenhaften sind das Abgründige und das Unheimliche jedoch ebenso präsent wie das Wissen um das Scheitern von Utopien. Die Künstler bedienen sich für ihre Arbeiten nicht nur der Malerei, sondern auch der Schlüsselmedien der Postmoderne wie Fotografie und Installation. Max Hollein und Martina Weinhart, Kuratoren der Ausstellung: "Die neue Romantik ist überall, in den Künstlerateliers in London, New York und Berlin. Aus dieser Fülle künstlerischer Ausdrucksformen filtert die Ausstellung "Wunschwelten" die prägnantesten Positionen heraus. Dabei sind sich die jungen Künstler ihrer historischen Vorgänger ebenso bewusst wie der Debatten der letzten Jahre. Ihr vermeintlich revisionistischer Weg zurück zu einem emotionalen Ausdruck bewegt sich insofern nicht abseits, sondern inmitten des aktuellen Diskurses und macht sie zu Seismographen der Sehnsüchte, aber auch der Ängste unserer Gesellschaft". Keine andere Epoche der deutschen Geistesgeschichte hat so viele Missverständnisse provoziert wie die Romantik. In der Alltagssprache wird der Begriff in der Regel verkürzt gebraucht und lediglich als sentimental, zivilisationsfern, stimmungsvoll, schwärmerisch und pittoresk ausgelegt. Mit der Komplexität der eigentlichen Bewegung hat dieses Verständnis kaum mehr etwas gemeinsam. Die Romantik ist nicht nur paradiesisch und schön, sie umfasst auch das Subversive von Entgrenzungserlebnissen, wie es uns in der Poetisierung der Welt bei Novalis oder den Gebrüdern Schlegel begegnet. Die Romantik findet sich bei E. T. A. Hoffmann in düsteren Entwürfen unheimlicher Gegenwelten, bei Caspar David Friedrich in symbolisch aufgeladenen Landschaften und in den beunruhigend visionären Traumbildern von Johann Heinrich Füssli. Ferner steht sie für die tiefe Skepsis der Jugend gegenüber den starren Konventionen des Akademiebetriebs und den Ruf nach künstlerischer Autonomie, wie von Philipp Otto Runge geäussert. Als emotionales Symptom einer gesellschaftlichen Realität, die bereits im 19. Jahrhundert durch politische und wirtschaftliche Umbrüche geprägt war, bildet das Romantische eine Parallele zur Gegenwart. Die heutige Künstlergeneration antwortet auf die Umstrukturierung politischer Systeme und den Verlust von grossen gesellschaftlichen Entwürfen mit einer Ästhetik der Ausseralltäglichkeit. Dieses transitorische Moment produziert ein Vokabular der Sehnsucht, dessen Grundstock in der historischen Romantik angelegt ist. Einsamkeit als romantisches Grundgefühl - dieses zentrale Thema findet vor allem in der Darstellung der Landschaft und deren Aufladung mit symbolischen Qualitäten seine Umsetzung. Hier stösst man in der aktuellen Kunst auf eine Vielzahl von Formulierungen, die von der Bedrohung bis zur Beschwörung der Idylle, der Überwältigung durch die äussere Unermesslichkeit und von der Natur als Anschauungsraum für das Transzendente berichten. So treiben Catherine Opies Surfer als kleine Punkte in der Unendlichkeit des Ozeans. Wenig dramatisch verschmelzen in diesen Fotografien die Wellen mit dem Grau des Himmels. Umso mehr scheint der Mensch im Diffusen dieses kaum stofflichen Raumes zu verschwinden, in dem es keinen Halt gibt. An den Spass der zeitgenössischen Freizeitindustrie gibt es hier trotz des Sujets nicht den geringsten Anklang. Auch Christopher Orr setzt seine Protagonisten dem Diffusen von Nebel und Nacht aus. Die Natur tritt lediglich als zeichenhaftes Versatzstück in Erscheinung. Den Figuren bleibt das spirituelle Verklärungspotenzial verwehrt: Sie sind in einer unergründlichen Distanz zur Natur gefangen und artikulieren damit einen Kern des romantischen Diskurses. Doch obwohl Orrs Gemälde auf den ersten Blick C. D. Friedrichs Forderung, der Maler solle nicht nur malen, was er vor sich, sondern was er in sich sieht, gerecht zu werden scheinen, entpuppen sie sich wie die Bilder der anderen Künstler der neuen romantischen Generation bei näherer Betrachtung in dieser Hinsicht als trügerisch. Die Künstler entnehmen ihre Motive nicht ihrem Innersten, sondern alten Zeitschriften, Magazinen, Filmen und ähnlichem Referenzmaterial. Jenseits vordergründigen Zitierens und Kontextualisierens werden die Versatzstücke zu Traumbildern mit einer offenen und assoziativen Struktur. Peter Doigs Rückenfigur eines Malers samt Staffelei vor einer eindrucksvollen Bergkulisse ist somit weniger ein Selbstporträt des Künstlers als ein Amalgam aus Imagination und historischer Fotografie. Heute ist der mediale Filter für die Künstler zur Selbstverständlichkeit geworden. Das ist die Botschaft der Postmoderne an die unmittelbare Erfahrung der Natur in der historischen Romantik. Auch Kaye Donachie verwendet visuelle Zeugnisse von unterschiedlichen Personengruppen, Kommunen und Gegenkulturen, die sie Dokumentationen und Super-8-Filmen entnimmt. In der Aneignung vorhandener Bilder thematisiert sie die gesellschaftliche Überschreitung oder ein romantisches Aufbegehren, das die Faszination der heutigen romantischen Generation für Gegenentwürfe und Alternativkulturen der 1970er Jahre reflektiert. Auch Justine Kurland greift in ihren Fotografien von Aussteigerkommunen im ländlichen Amerika die Utopien der Hippiegeneration auf und setzt sie wie Relikte einer vergangenen Zeit ins Bild. Das Symbol der Anarchie, das Mitte der 70er Jahre auf dem Höhepunkt der Anti-Establishment-Bewegung die Massenmedien und das Bewusstsein der westlichen Teenager eroberte, kombiniert Simon Periton in seinen Scherenschnitten scheinbar mühelos mit der Biedermeierlichkeit einer fragilen Blumengirlande. In seiner verspielten Virtuosität Runge'scher Prägung ruft Periton den utopischen Aspekt der Romantik auf und verbindet ihn mit einer konkreten politischen Botschaft. Schliesslich fassen Künstler wie Uwe Henneken, David Altmejd, Christian Ward und Karen Kilimnik die Romantik in einem popkulturellen Kontext auf. Bei Henneken sind die Motive oft überzogen inszeniert, mit einer Farbgebung, die den Kitsch nicht scheut. In den Bildern von Laura Owens scheint nicht selten der Vollmond durchs Geäst; auch sie ängstigt sich nicht vor der aufgeladenen Plakativität solcher Embleme und versteht sie wie alle anderen zu brechen und in ein radikales zeitgenössisches Vokabular zu überführen. Vor diesem Hintergrund erweist sich die Romantik als Verfahren, das in unterschiedlichsten Linien und Strategien der Aneignung von den heutigen Künstlern aufgenommen, fortgeführt und transformiert wird. Dabei geht es um weit mehr als um die Wiederbelebung einer Skala von Motiven, die als wehmütige Versatzstücke einer glorreichen Vergangenheit in die zeitgenössische Kunst herübergerettet werden. Die heutige Romantik ist eine Metaromantik mit den Mitteln der Postmoderne. Sie schafft eine Synthese aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, aus Emotion und Diskurs. Katalog: "Wunschwelten. Neue Romantik in der Kunst der Gegenwart". Hg. von Max Hollein und Martina Weinhart. Mit einem Vorwort von Max Hollein, Essays von Rainer Metzger, Beate Söntgen, Martina Weinhart und Texten von Will Bradley, Ralf Christofori, Katharina Dohm, Dominic Eichler, Barbara Hess, John Kelsey, Anke Kempkes, Francesco Manacorda, Christopher Miles, Martina Weinhart. Deutsch/englisch, 304 Seiten, 78 Farb- und 12 Schwarzweissabbildungen, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2005, ISBN 3-7757-1590-8. Die Ausstellung wurde durch die Sireo Real Estate Asset Management GmbH gefördert. Zusätzlich wurde sie durch das Mercure Hotel & Residenz Frankfurt, das Novotel Frankfurt City West, das British Council und die Botschaft von Kanada unterstützt. Ausstellungsdauer: 12.5. - 28.8.2005 Öffnungszeiten: Di, Fr-So 10 - 19 Uhr, Mi/Do 10 - 22 Uhr Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt Römberberg D-60311 Frankfurt am Main Telefon +49 69 29 98 82-0 Fax +49 69 29 98 82-240 Email welcome@schirn.de www.schirn.de Ideal Worlds New Romanticism in Contemporary Art David Altmejd, Hernan Bas, Peter Doig, Kaye Donachie, Uwe Henneken, Karen Kilimnik, Justine Kurland, Catherine Opie, Christopher Orr, Laura Owens, Simon Periton, David Thorpe, Christian Ward In a society marked by increasing mobility and waning social bonds, a new yearning for intimacy and security prevails. The flood of bad news and images of terror makes people long for safe places and redemptive perspectives. This situation is also reflected in today's visual arts. After the analytic explorations of discourse in the 1980s and 1990s and the remaking of art into a social act, we are confronted with a revival of the traditional work wherever we turn to. Artists such as Peter Doig, Laura Owens, Uwe Henneken, David Altmejd, Kaye Donachie, Karen Kilimnik, Justine Kurland, or David Thorpe have clearly taken up a thread of the Romantic spirit. Yet, behind the desire for the paradisiacal, the beautiful, and the magic of fairy-tales, the dark and the eerie are as present as the insight that Utopias are doomed to failure. The artists do not only rely on painting for their works, but employ the key media of postmodernism like photography and installation. Max Hollein and Martina Weinhart, curators of the exhibition: "The new Romanticism seems to be omnipresent, whether in the studios of London, New York, or Berlin. Drawing on this wealth of artistic forms of expression, the exhibition "Ideal Worlds" focuses on the most striking examples. The young artists are as aware of their historical predecessors as of recent years' discussions. From that point-of-view, their supposedly revisionist return to an emotional mode of expression is far from aloof but right in the center of today's discourse and makes them seismographs of this society's longings and fears." No other period of German intellectual history has produced as many misunderstandings as the Romantic movement. In everyday language, the term is generally used in a reduced sense meaning sentimental, far from civilization, full of atmosphere, rapturous, picturesque. This use has only little to do with the actual movement's complex character. The Romantic spirit aims at more than the paradisiacal and the beautiful; it also includes the subversive tenor of transcending limitations we find in the poeticization of the world by Novalis or the brothers Schlegel. While the Romantic manifests itself in the form of gloomy sketches of uncanny counter-worlds for E. T. A. Hoffmann, Caspar David Friedrich confronts us with symbolically charged landscapes and Henry Fuseli with irritating dream visions. The Romantic also stands for young people's deep skepsis about the rigid conventions of academic institutions and the call for artistic independence as uttered by Philipp Otto Runge. As an emotional symptom of a social reality already informed by political and economic upheavals in the 19th century, it definitely provides a parallel with the present-day situation. Today's generation of artists counters the restructuring of political systems and the loss of comprehensive social plans with an aesthetics beyond the ordinary. The aspect of transition creates a vocabulary of yearning rooted in the historical Romantic movement. Loneliness as an essential Romantic outlook - this central subject is mainly dealt with in the form of sceneries charged with symbolic qualities. Contemporary art encompasses numerous variations of this theme which range from the threatened idyll and its invocation to the overwhelming impression of outer vastness and nature as a space for regarding the transcendental. Catherine Opie's surfers are just little points against the infinity of the ocean. In these photographs, the waves blend into the grey sky in a quite matter-of-fact way. Thus, man seems to disappear all the more in the vagueness of a material space offering no support. In spite of the subject, there is no echo of the fun of today's leisure industry. Christopher Orr also exposes his protagonists to the confusion of haze and the dark. Nature has been reduced to a symbolic prop. The figures are not granted any chance of spiritual transfiguration: caught in an inscrutable distance from nature, they give expression to a key issue of the Romantic discourse. Though, at first sight, Orr's paintings seem to comply with C. D. Friedrich's request that painters should not only paint what they see in front of them but also what they see inside, his works reveal themselves as deceptive in this regard just like the works by the other artists from this generation of new Romanticists when you have another look. The artists' motifs do not stem from deep down inside them but from old newspapers, magazines, films, and similar sources. Apart from superficial quoting and contextualizing, the individual elements are translated into dream visions characterized by an open and associative structure. So Peter Doig's figure of a painter seen from behind and facing an impressive mountain scenery rather amalgamates imagination and historical photography than presenting a self-portrait of the artist. Today's artists have got used to the filter of the media. This is the postmodern message concerning the immediate experience of nature in the Romantic period. Kaye Donachie also employs visual evidence from different groups of persons, communes and counter-cultures, which she takes from documentaries and super-8 films. Appropriating existing images, she focuses on overstepping limits and a Romantic revolt that mirrors the fascination of today's Romantic generation for the alternative concepts and cultures of the 1970s. Justine Kurland's photographs of dropout communes in rural America also relate to the Utopian ideas of the hippie generation and present them like relics of a past era. In his cut-outs, Simon Periton combines the symbol of anarchy, which conquered the mass media and won the Western teenagers' hearts at the peak of the anti-establishment movement in the mid-seventies, with the Biedermeier character of a fragile festoon in a seemingly effortless fashion. With a playful Runge-style virtuosity, Periton recalls the Utopian dimension of the Romantic period and links it with a concrete political message. Finally, artists like Uwe Henneken, David Altmejd, Christian Ward, and Karen Kilimnik explore the spirit of Romanticism in a pop-cultural context. The colors of Henneken's frequently exaggerated presentations do not shrink from kitsch. We often see the full moon shining through the branches in Laura Owen's pictures: she is not afraid of the charged directness of such emblems either and, like the others, knows how to break them and convert them into a radical contemporary vocabulary. Considering these contexts, Romanticism presents itself as an approach which has been taken up, continued, and transformed in a variety of lines and strategies of appropriation by today's artists who aim at much more than at reviving a gamut of motifs saved as melancholy props from a glorious past. Today's Romanticism is a meta-Romanticism working with postmodernist means. It unfolds a synthesis of past and present, emotion and discourse. Catalogue: "Ideal Worlds. New Romanticism in Contemporary Art". Edited by Max Hollein and Martina Weinhart. With an introduction by Max Hollein, essays by Rainer Metzger, Beate Söntgen, Martina Weinhart, and texts by Will Bradley, Ralf Christofori, Katharina Dohm, Dominic Eichler, Barbara Hess, John Kelsey, Anke Kempkes, Francesco Manacorda, Christopher Miles, Martina Weinhart. German/English, 304 pages, 78 color and 12 black and white illustrations, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2005, ISBN 3-7757-1590-8. The exhibition was sponsored by Sireo Real Estate Asset Management GmbH. It was also supported by Mercure Hotel & Residenz Frankfurt, the Novotel Frankfurt City West, the British Council, and the Canadian Embassy. Exhition: 12 May - 28 August 2005 Opening hours: Tues, Fri-Sun 10 am - 7 pm, Wed/Thu 10 am - 10 pm |